Industrial - Bachelor

Empathetic Design in Humanoid Robotics

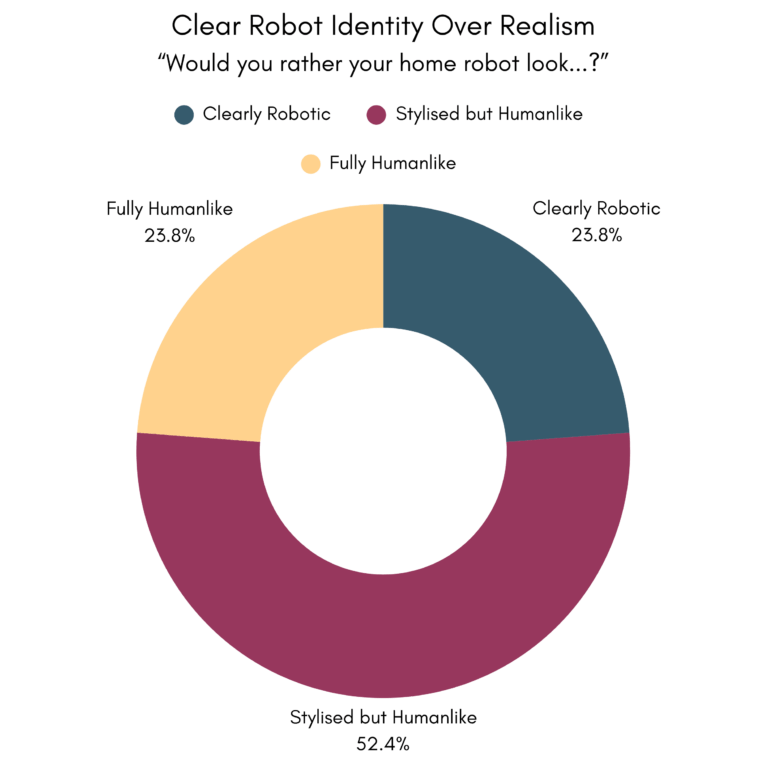

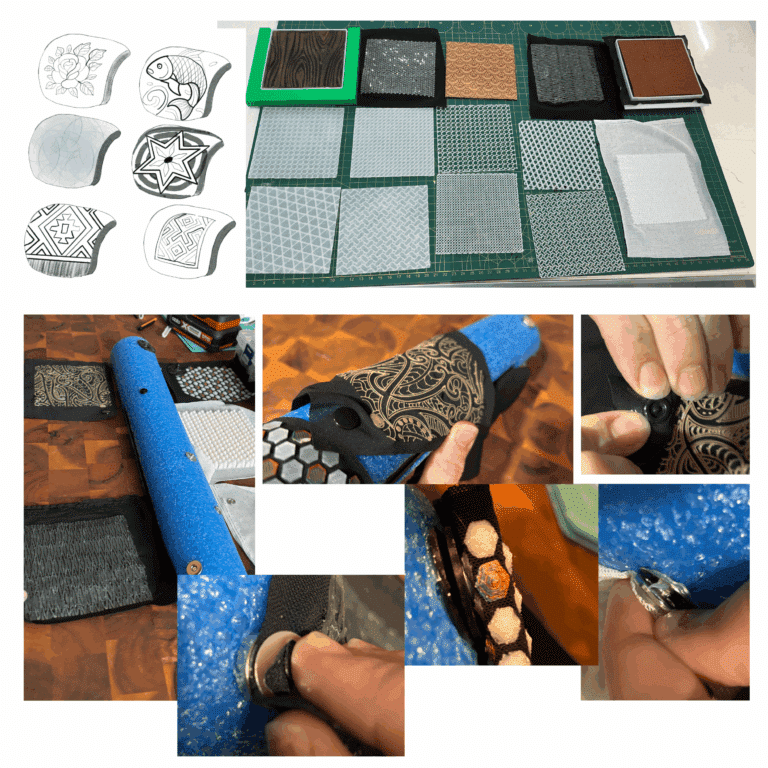

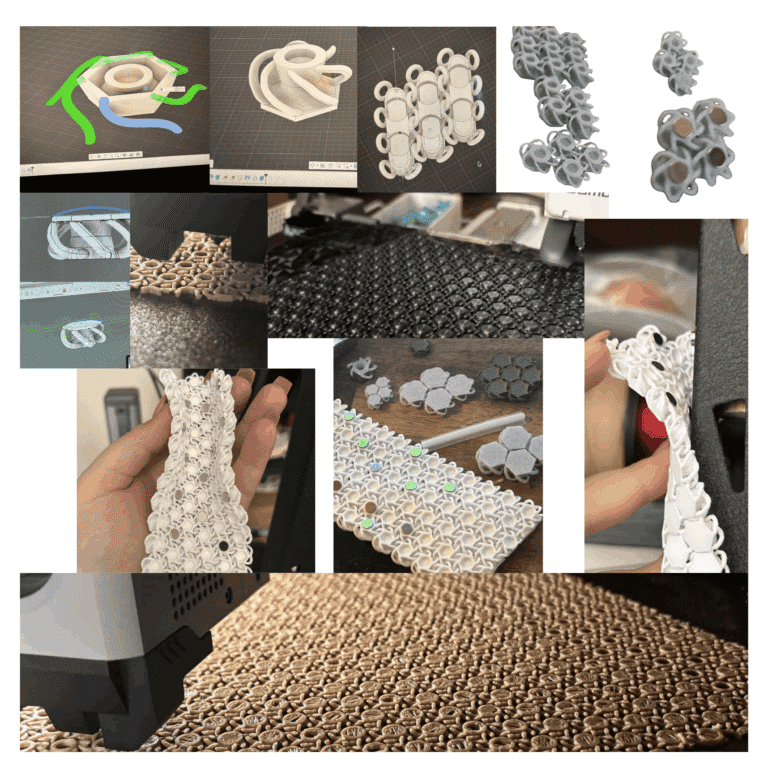

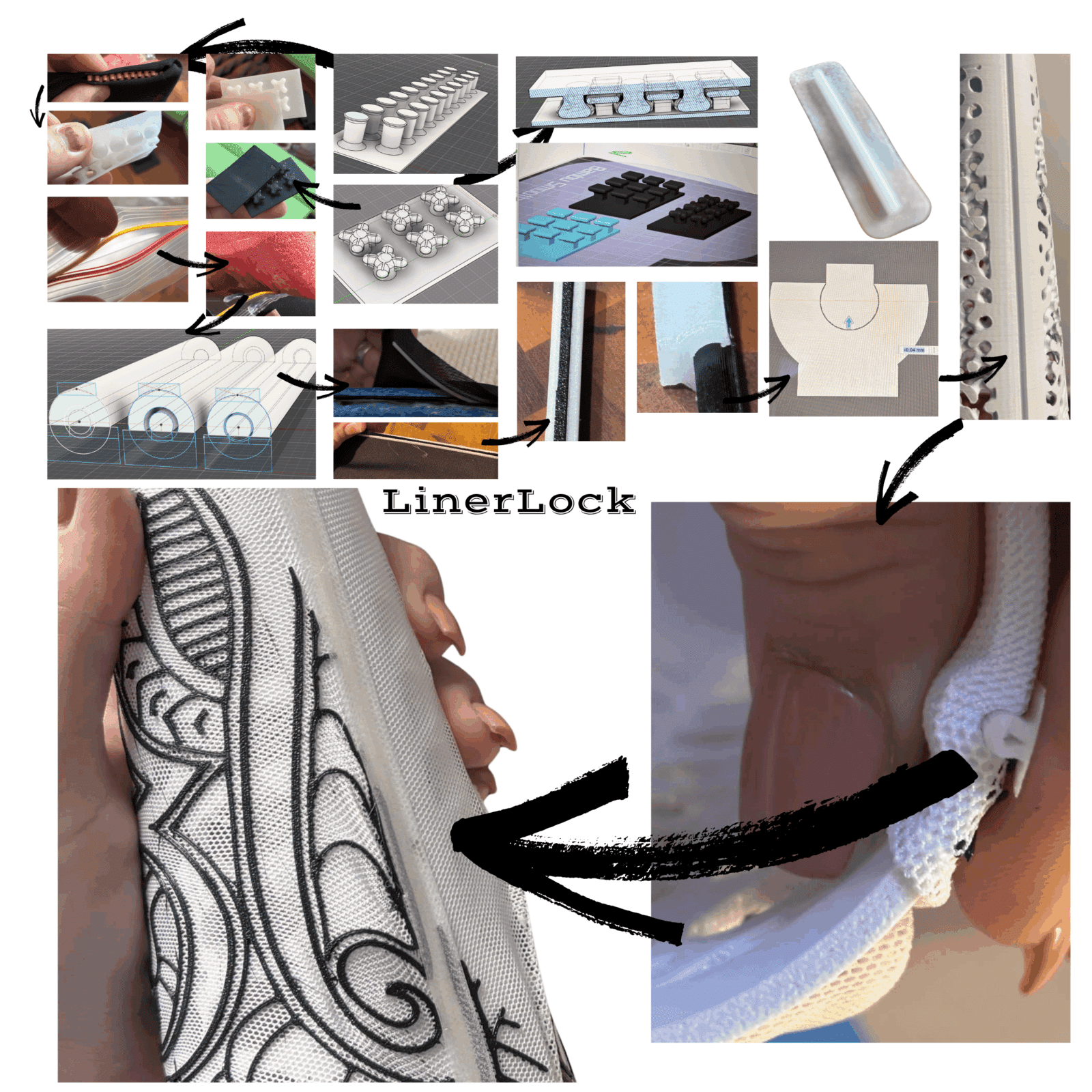

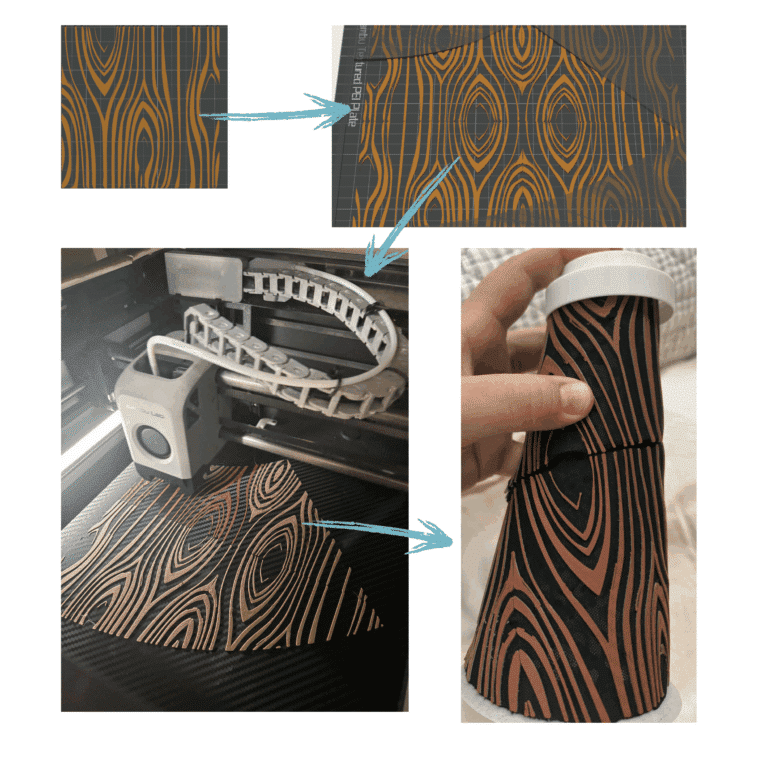

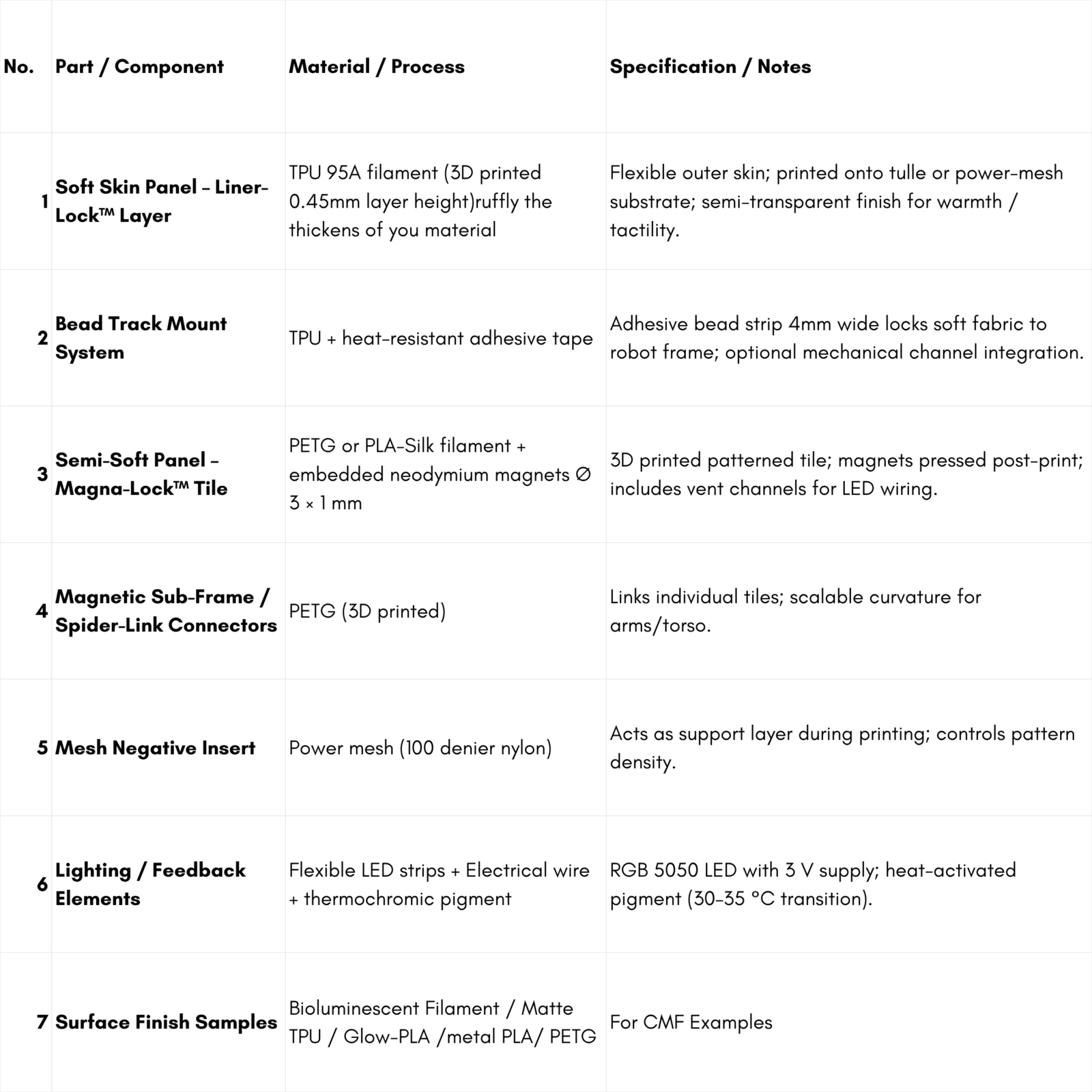

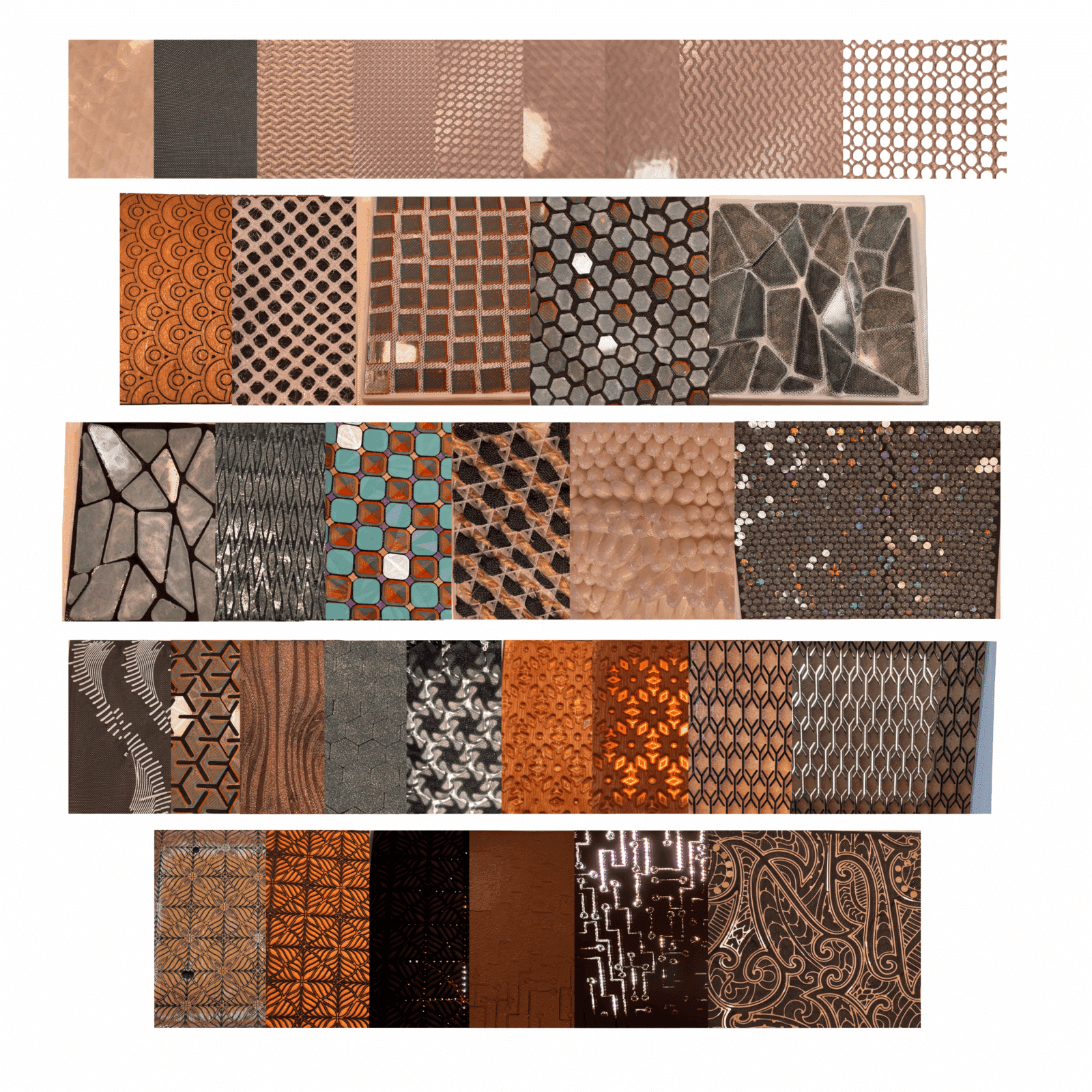

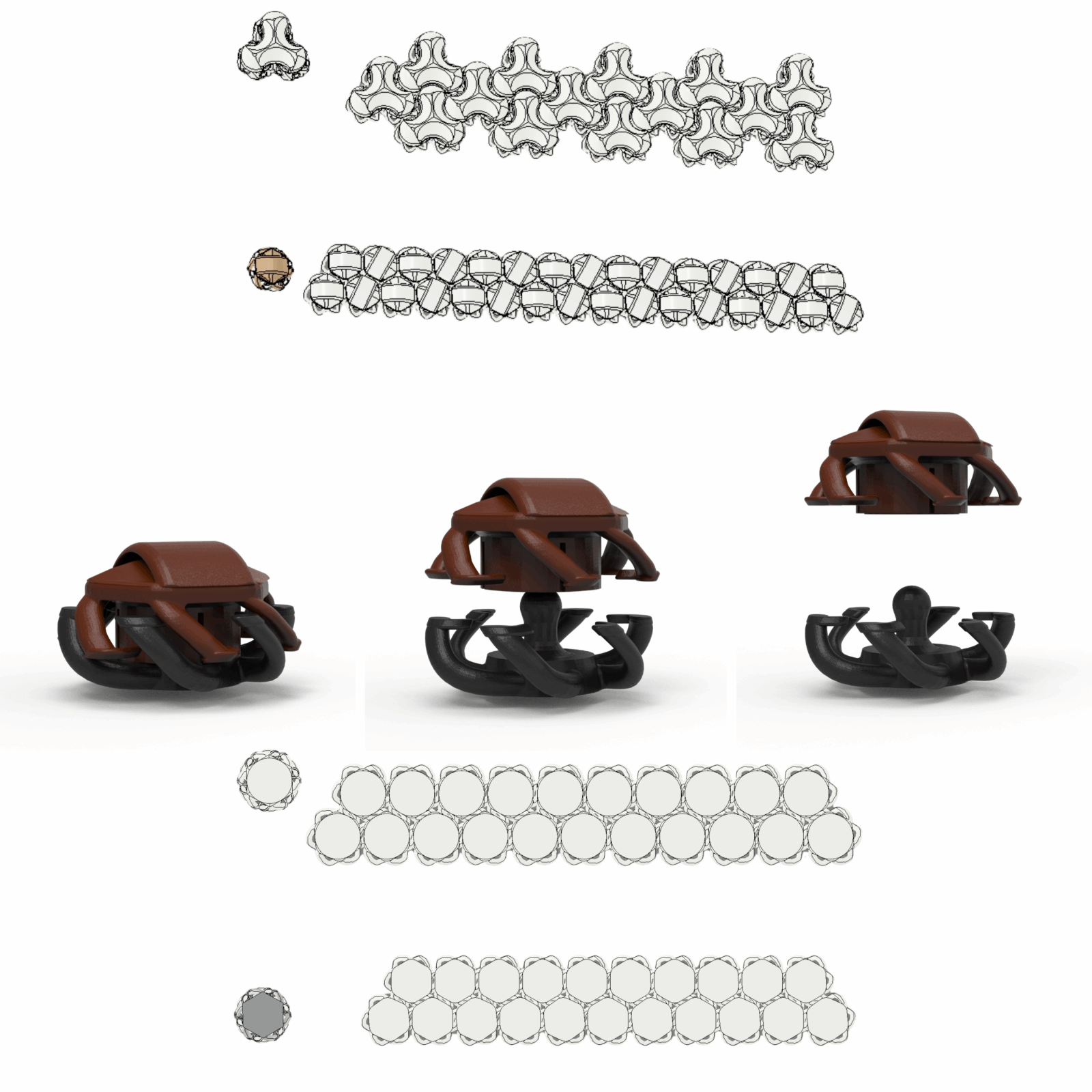

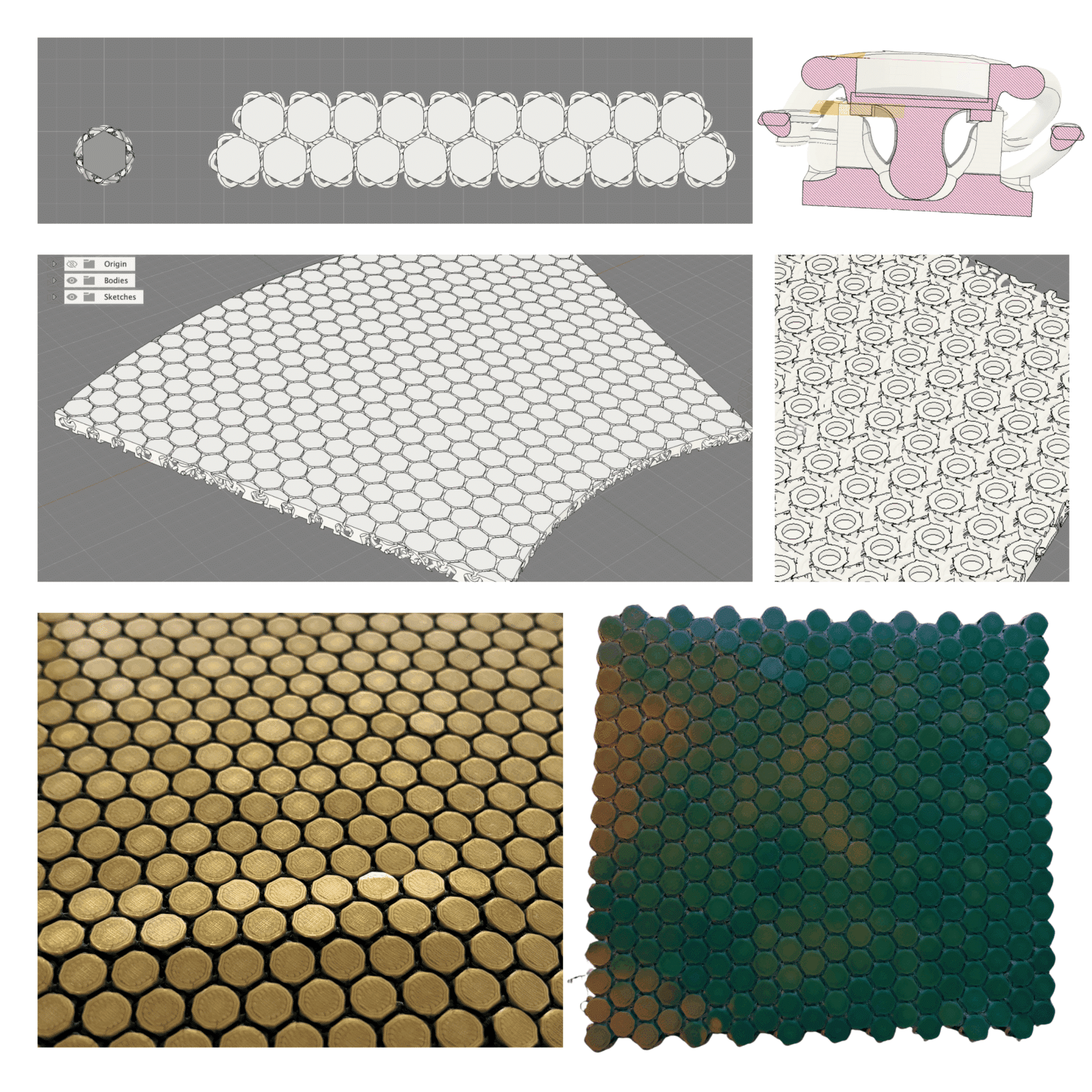

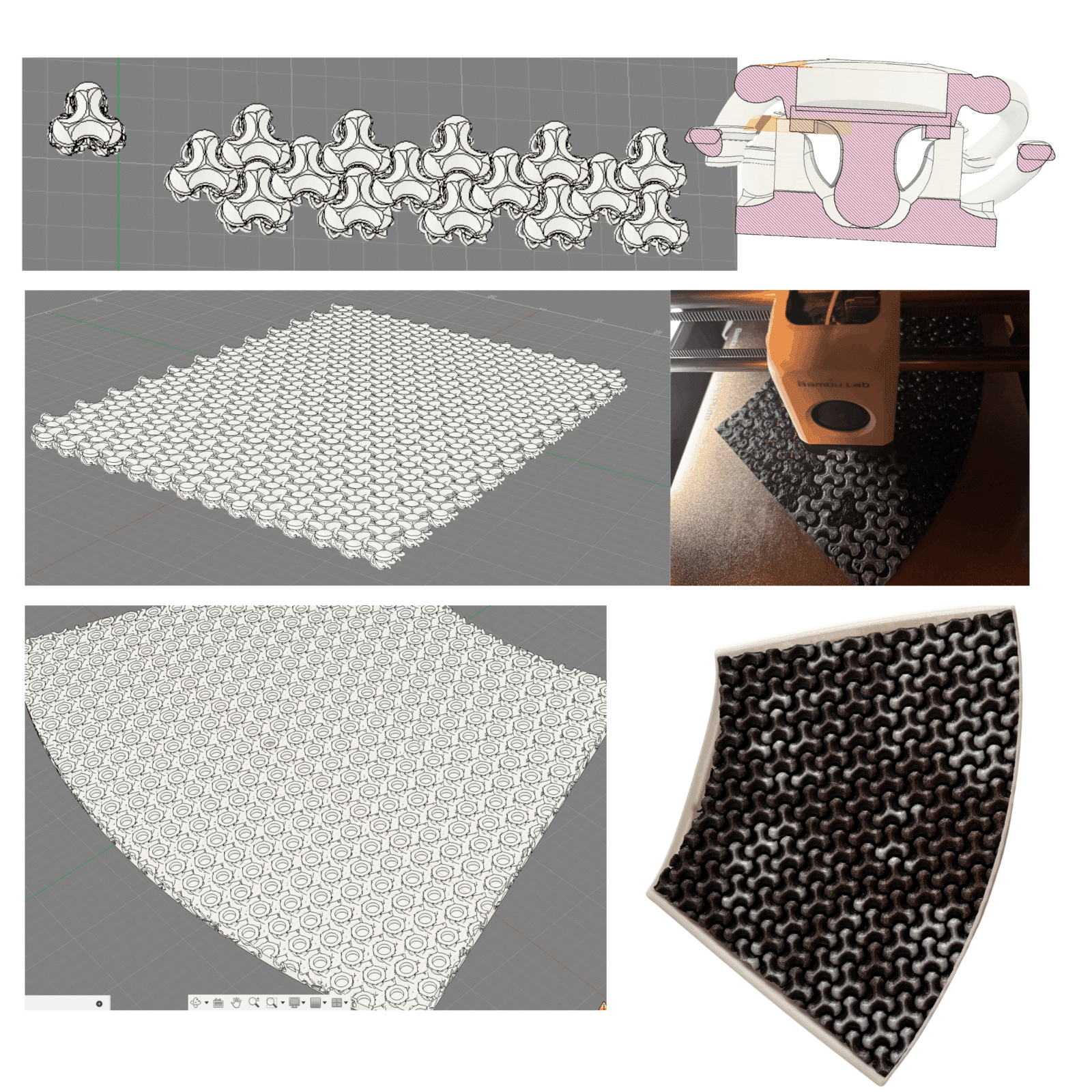

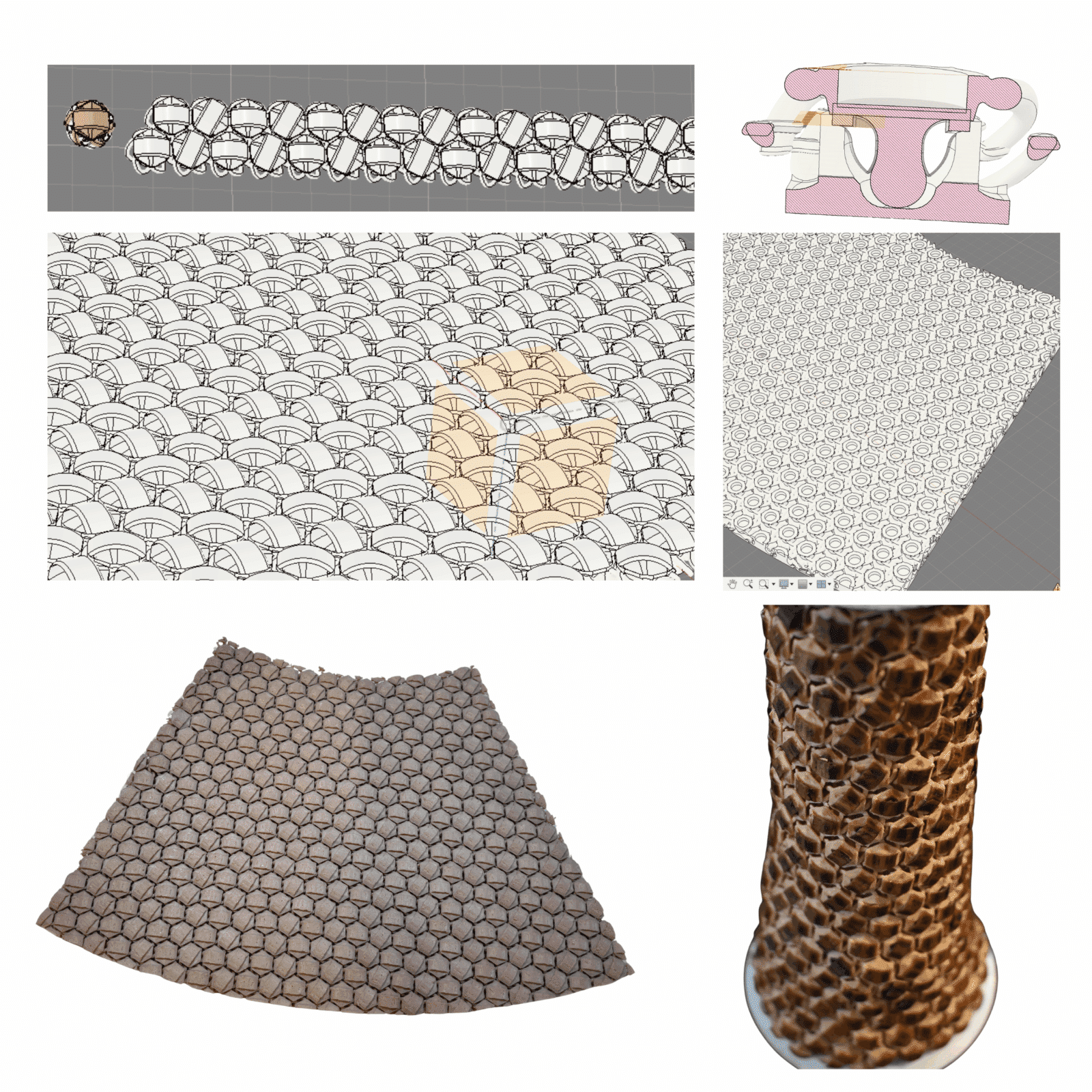

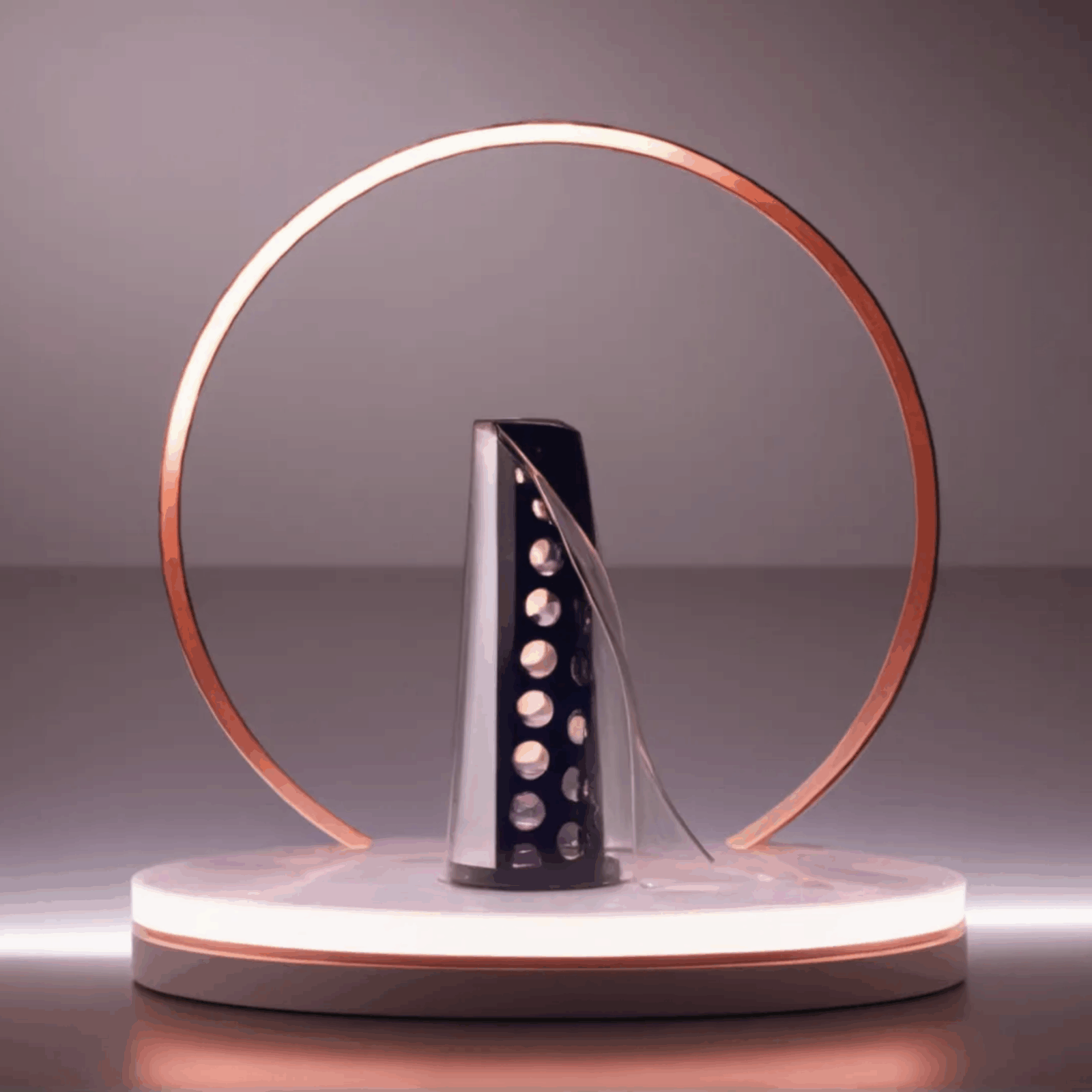

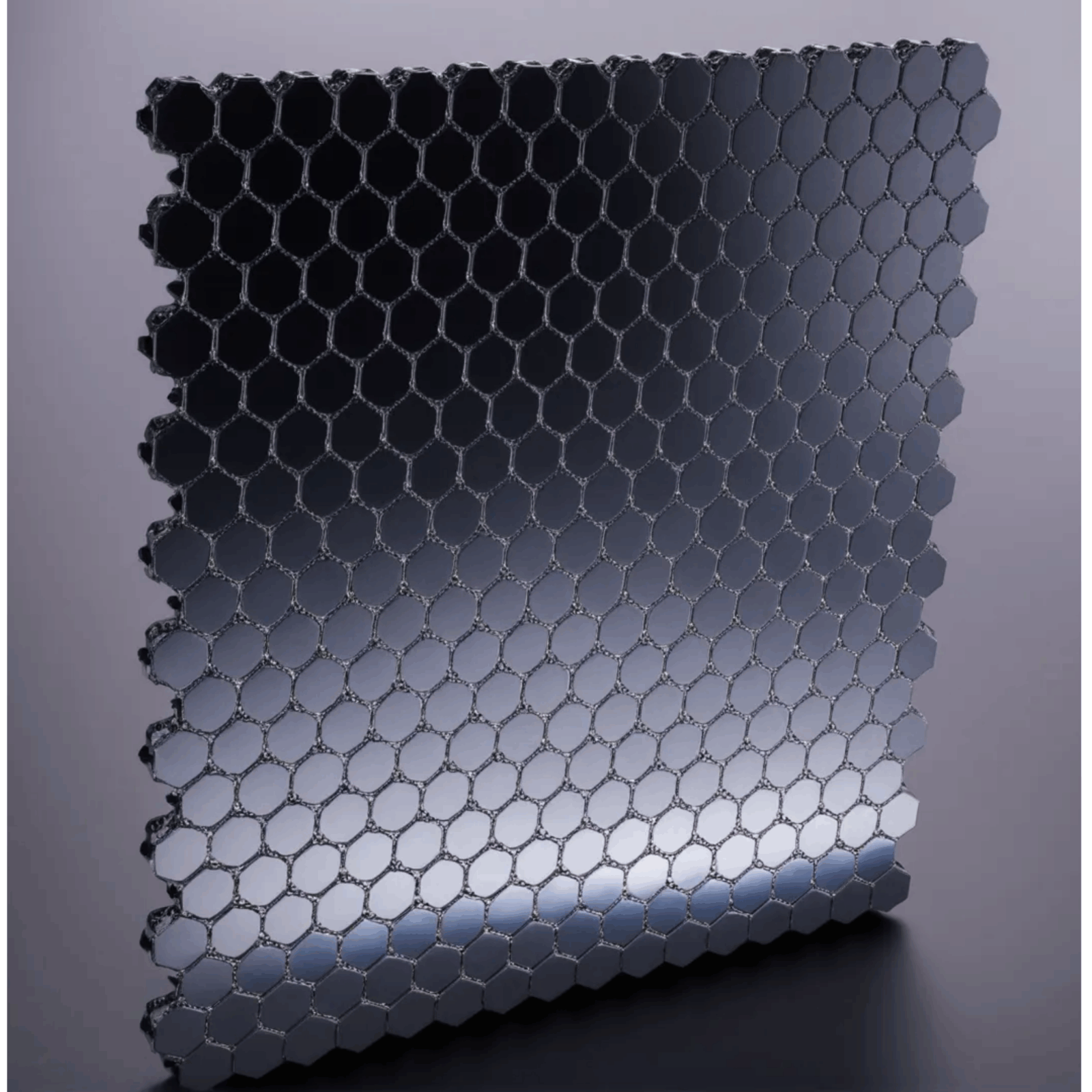

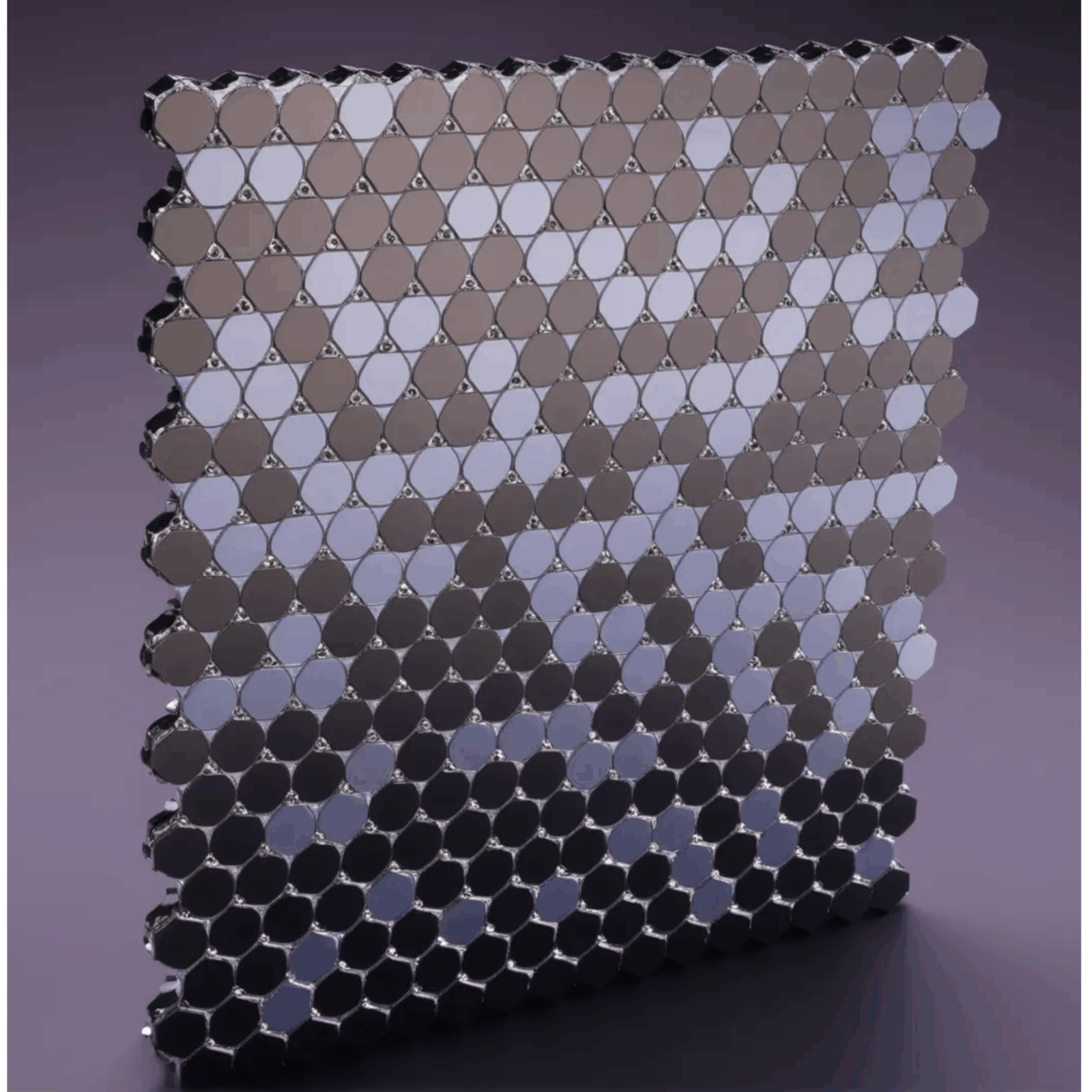

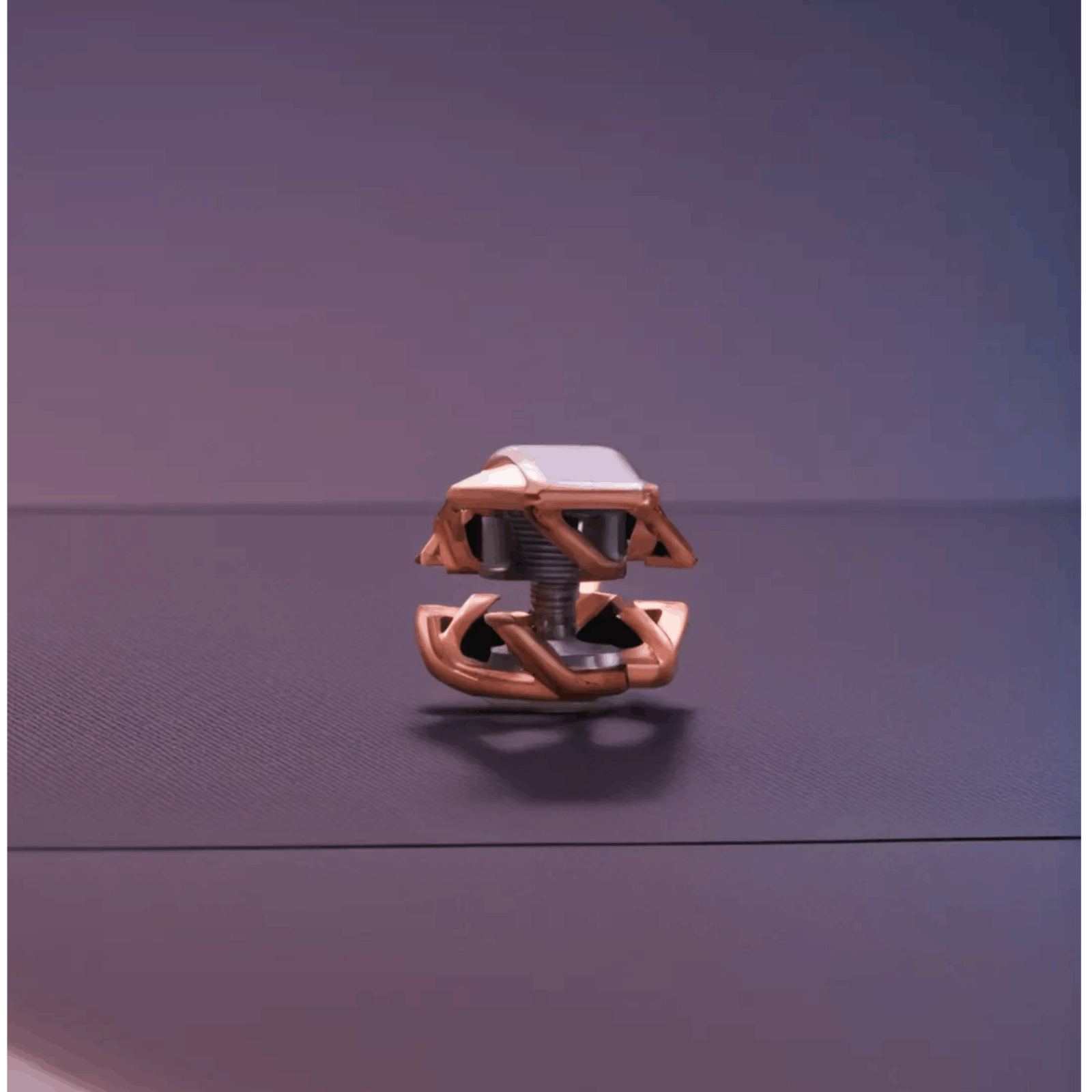

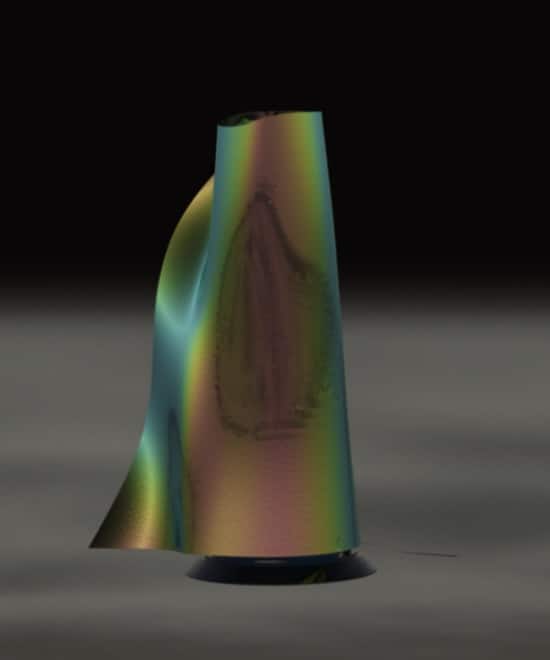

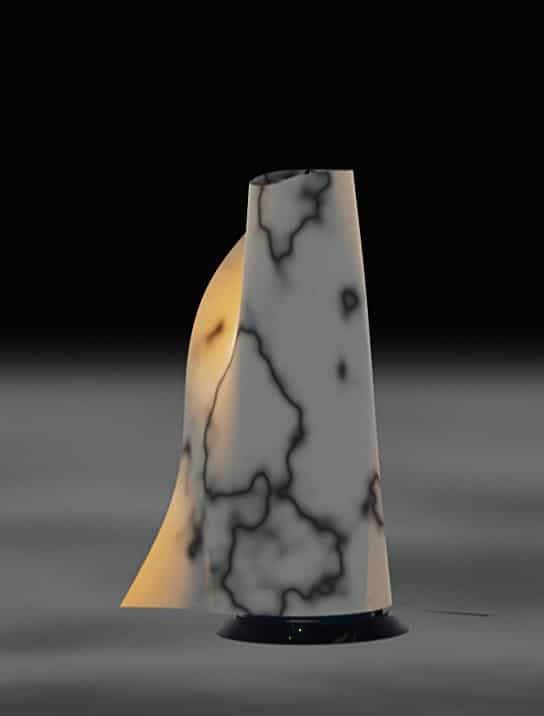

The successful integration of humanoid robots into domestic environments hinges not only on their technical performance but critically on their acceptance by human occupants. This project investigated how strategic application of colour, material, and finish in a robot’s cladding can foster human comfort, trust, and emotional connection, moving beyond traditional industrial aesthetics.